This post, the Auschwitz post, has been incredibly challenging for me to write. Not because of the grim subject matter; everybody knows, to some degree, what happened at Auschwitz. However, far too many people are comfortable with their limited knowledge, aware the Holocaust took place, but uninterested in the details. Willful ignorance, a turning of the other cheek, was in large part the reason the Nazi’s were able to torture and murder six million human beings.

I have come to know plenty of willfully ignorant people, folks who refuse to inform themselves not just about the horrors that occurred in past, but also, about the atrocities that are being committed right now, at this very moment, around the world. For them, the subject is uncomfortable, but more so, and far more disturbingly, these things are inconsequential because they are happening to “other people.” That mentality led to Jews being herded into ghetto’s, right under their neighbors very noses, and sometimes, at their behest. Neighbors who had been whipped into a hateful frenzy, who refused to think about or deal with the implications, comfy with their own circumstances. I see that same scape-goat mentality today, as more and more people reach an anti-Muslim fever pitch.

I’m a secular Jew. And by Secular, I mean atheist. However, I have always strongly identified with my Jewish roots, with Jewish culture, which I have always revered and have always, always, felt privileged of which to be a part.

During the years of my primary education, the Holocaust was the focus of study for one week, every year. I have attended more Bar and Bat Mitzvah’s in my life than I have weddings. I grew up in an area so Jewish, anti-Semitism seemed overstated; something that super sensitive Jews harped on about. It is not; I began to understand that when I left for college and experienced my first encounters with anti-Semitic hate speech.

When I met my husband, who is from Iowa, his Holocaust awareness at the time was on the “it existed” level, and that was about it; the same was true of his Iowan family and friends. I just could not understand how that could be. In fact, I was the fourth Jew he had ever met in his life, the first three being members of the same family. The Holocaust was simply not taught in Iowa schools, and I would venture to guess that’s the case in most of the non-coastal states, where the Jewish population is next to none. Jewish culture has become a way of life for him now, his wife, mother-in-law, siblings-in-law, niece, and best friends are all Jews. He’s been to Hanukkah dinners, Bar Mitzvah’s, and Jewish weddings. Most importantly, he has been to Auschwitz.

My hope is that with the development of virtual reality tools such as Oculus Rift, everyone, will in some fashion, visit Auschwitz. “Never forget” is not a meaningless catch phrase; a vigilant understanding of what happened in Nazi Germany and how it happened, is a matter of utmost importance; without it, history is locked, loaded, and ready to repeat itself. I have met many fine people who are not at all stirred by the atrocities that transpired out in the Polish countryside. I can only conclude this is due to a lack of understanding, beyond the murder of six million people, what took place. That kind of ignorance shocks me. Every. Single. Time.

Auschwitz.

Most people visit by tour bus; we chose to hire a cab for our trip, so that we would have the freedom to do as we wanted with our day. Oswiecim is the actual name of Auschwitz; the Polish name. When the Nazi’s rolled into town, they gave it a German moniker, as they frequently would in occupied areas. The town is roughly one hour by car outside of Krakow, through the lovely, rural, green, countryside, dotted with charming country homes.

I could not help but picture the trains packed with scared, filthy, Jews, some of them already dead; cars that reeked of urine and excrement and fear, children and babies crying and screaming; cars loaded so full that the occupants were unable to sit for the journey which often lasted days, the occupants taking turns pressing their mouths to small holes, trying to gulp precious, life sustaining air. I thought of those trains rolling through this ironically beautiful place, delivering human cargo to the last horrific moments, days, or months of their lives. I pictured terrified escapees, running through the deadly cold winter, scared out of their minds, seeking refuge.

Upon arrival, all visitors start in a ticketing room where water and restrooms are available. Visitors who arrive prior to 3PM can only see Auschwitz by tour; it is not a visit one should make without a guide at any rate. Tour groups are arranged by language; the guide wears a mic, the attendees, headphones; this allowed us to hear what was being said with terrific clarity, the voices of the others guide’s being blocked out.

We started at the infamous sign that has come to symbolize Auschwitz the world over; Arbeit Mach Frei (Work Makes you Free)

Our guide began by asking what nationalities were present in our group, in order to make a connection between all of us and the victims who lost their lives at Auschwitz. Already, I was crying. The weight of that place, standing under the sign I’d seen in so many movies and books; it was chilling.

The English were the first to use the term concentration camp; to them, it was a place to quarantine a certain group from the rest of society, no more, no less. The Germans “developed” the word to mean death camp; The purpose of Auschwitz was never work, but rather death. The entire point and purpose, death. The Nazi’s, with efficiency in mind, were sure to utilize the full spectrum of resources that each prisoner possessed; their money, belongings, power, strength, mental health, until all was exhausted; then, when they were of absolutely no use, they would either die “naturally” or they were murdered. The sign was meant to be snarky. Freedom was never an option, save the freedom of death.

The Auschwitz orchestra was explained to us, something I had not known existed.

The orchestra was comprised of inmates with musical talent; they played on many occasions; Nazi holidays, inspection days, public punishments, executions, private performances for the camp guards, but their main task was to play as their fellow inmates marched to work in the morning, and again when they returned in the evening. The Nazi’s felt this would keep the laborers moving at a certain tempo, but it also helped keep inmates in a countable formation. The prisoners, of course, felt tortured by the sound of this music every morning, songs like “The Best Times of My Life” playing as they were slowly being worked to death. By one account, a woman returned from work, holding the dead body of a comrade in her arms, trying to keep tempo with her left leg to the sound of the orchestra, so as not to upset her captors. In Birkenau, the orchestra was forced to play during the arrival and selection process, literally providing the soundtrack as other Jews were being herded to the crematoria.

We walked to cell block four, an entire two story building dedicated to educating visitors about the Nazi methodology for extermination.

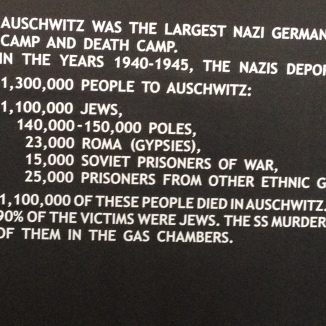

Our guide told us about how the Nazi’s came to the conclusion that they should round up Jews, gypsies and German “enemies,” the communications over what to do with them and why, and finally, how the process was executed. The first room in the cell block displayed a map showing all of the European cities from where the victims came; beside that, a written accounting of the numbers; 1,300,000 victims were brought there, 1,100,000 of whom were murdered, 90% of whom were Jews. The world’s largest cemetery.

There was an urn atop a marble column in that room; it held a mix of ashes, all that was left of the dead when the camp was liberated. The existence of one million people, reduced to this tiny collection of remains.

This room also contained the original document that ordered the Final Solution of the Jewish question; the written directive to murder Europe’s eleven million Jews. Seeing it in front of me, even though I couldn’t comprehend the language, was dizzying. Something so small and physically inconsequential; a piece of paper, set into motion the process that would end in the death of six million human beings. Had I lived in Nazi Germany, this would have been an order for my death, my parents death, my siblings death, my friends death. It made me sick, looking at that paper.

In another room, the selection process was explained. Our guide, who very much wanted us to relate on a personal level, implored us to empathize with the humans who died there. He pointed to the blown up photos, pointed at faces, asking the group, “this woman, what did she do to the Nazi’s? She did nothing and she paid with her life.”

Viewing those photos was a devastating experience. One picture depicted two columns of people; women on one side, men on the other. The guards in the picture look very blasé, standing around smoking cigarettes; they display no signs of aggression, working to give the impression that nothing alarming was about to take place. These photos depict the last moment these people, these families, mothers, children, siblings, fathers, would ever see one another again.

Another photo showed two children with their mother, all of them holding hands, fresh arrivals walking unknowingly to the gas chamber. Behind them walked a woman with an infant in her arms. Children were killed, many upon arrival, because they were too young and physically weak to be of any value as workers but also, because they had the capacity to become future enemies. Their mothers were murdered along with them because the Nazi’s had discovered that women who lost their children were unable to go on, rendering them useless as laborers.

It was said that some 650,000 children were murdered at Auschwitz, many in the gas chambers, some, picked up by the ankles for efficiencies sake, then swung against the side of a building to crush their skull, many more at the cruel hands of Dr. Joseph Mangele, as he performed unspeakable “medical” experiments on them.

One of the most poignant photos of all showed the actual selection process as it took place. A man with white hair and a cane stands in the front of a long line, facing a Nazi who points him to the right. The Nazi is pointing towards a group of men, all with white hair (seen in the upper right hand corner of the frame). Old, useless, people, unwittingly gathered outside of a death chamber. We were looking at this man being sentenced to death with the flippant flick of a wrist. It was gut wrenching.

We went to the second story of cell block four where we saw the models of gas chambers. The Germans were anything if not calculating and precise.

There were more blown up photos there; illegal photos that had been taken by an SS officer, one of which depicted naked Jewish women running, emaciated and clearly terrified. The photo below, if memory serves, shows Nazi’s working to destroy evidence at the wars end.

Piles of empty Zyklon B canisters sat on display, along with one that had been emptied out to show the actual crystals

From there, we were told that we were about to enter a room that contained human remains; photos were not allowed out of respect to the dead. The room was dark, with a wall of glass spanning the entire length of the building, behind which laid piles, upon piles, upon piles, of the victims hair; hair the Nazi’s had shaved off of the victims heads when they arrived at Auschwitz. The pile must have been five feet tall. As cliché as it sounds, I truly can’t describe how it felt; I just don’t have the words.

What followed was a series of similar “displays;” heaping mounds of the prisoners personal effects. Eyeglasses,

shoes, kitchenware, prayer shawls (tallit). The Nazi’s forced the Jew’s to clean machine guns with their prayer shawls, the ultimate violation of their faith and beliefs.

There were two piles of children’s effects; the clothes and tiny little shoes of murdered babies and toddlers.

Next we were taken to the living/sanitary conditions block. The most harrowing thing about that cell block, the thing I keep going back to, was the hallway lined with intake photos; mug shots of the prisoners in their stripes. Underneath the photos was captioned their name, date of birth, deportation date, and date of death. Most of the women lasted two to three months; most of the men four to six; there were a few rare exceptions who lasted nearly a year. I stood there staring into the eyes of one man; I felt like I knew him, like I could see him in his pre-Auschwitz life; I pictured him being torn from his family, then starved and worked to death, in the freezing Polish winter.

The prisoners were given 1300 calories daily on which to live, spending twelve hours per day performing hard labor. The Nazi’s took those intake photos to help them recognize a prisoner should they escape, but they learned that rather quickly, the inmates no longer resembled themselves due to starvation, which led to a change in tactics; the implementation of the numbered tattoo’s. Prisoners were not allowed to address each other by name. They were only to be known by their number.

When the women arrived, all of their body hair was shaved off both in an effort to humiliate and dehumanize them, but also to provide warm material for socks and winter coats for their Nazi captors. Many of them, best friends and even relatives, were unable to identify one another once the process of starvation, coupled with the removal of their name and identifying features was complete.

Winter temperatures in Poland average negative twenty degrees Celsius. Those poor souls tried to survive in that weather, hairless, working twelve hour days, with a mere thirteen hundred calories to sustain them.

We walked to block eleven next, where prisoners were punished, which reads like some cruel joke as I write it, as though everything else they were experiencing was not “punishment” enough.

There were starvation cells, sensory deprivation cells, and forced standing blocks. We were told of a priest who offered his life in place of another man, a father, who was to be killed in there. The priest was placed in a starvation cell, but he survived two weeks, frustrating the Nazi’s so thoroughly that they finally poisoned him to death. There was a candle in his cell, which remains lit; a memorial to his selflessness and needless suffering. The cells there, in the punishment block, were given access to air by holes to the outside; holes which would clog with snow in the winter, suffocating the inmate to death.

We were shown three columns, or cement boxes, maybe two feet square inside (the top half has been removed for viewing sake) where prisoners were forced to stand, all night long, in the pitch dark, with no room to move or sit. In the morning, they were taken to work all day, after which they were returned to the box, to stand throughout the night, then work in the morning, then the box at night, then work again. This cycle would continue for three straight days, after which the tortured inmate would reach their breaking point.

The basement of cell block eleven is where the Nazi’s first experiments with Zyklon B took place. The original dose was not lethal enough, causing the 850 test subjects to suffer two full, agonizing days before they finally died.

Outside of block eleven was the shooting wall, where the first mass killings at Auschwitz occurred. The wall now has flowers at its base, placed there by visitors.

The cell block windows facing the courtyard were boarded in order to block the other prisoners from witnessing the executions.

The courtyard was rimmed with poles from which men were hung, their arms pulled behind their backs, their wrists bound together then attached to the hooks, their feet unable to reach the ground. Eventually, this stress position caused their shoulders to dislocate, rendering them worthless, at which point they were murdered.

We walked by the once electrified barbed wire, onto which prisoners would throw themselves to commit suicide

up towards the guard tower, and out to the gas chambers.

We were able see Rudolph Hess’s home down the dirt road, and the gallows upon which he was eventually hanged, right there behind the guard tower.

10% of Nazi’s perpetrators were ever tried or punished.

I don’t have a picture from the right angle, but the roof of the gas chamber was covered in grass, giving it a completely benign appearance. This photo was taken from the other side; the entry to the chamber.

Inmates were forced to strip outside, often in the dead of winter, before being herded in to their death. Walking in there literally took my breath away. I’d seen images of gas chambers so many times, but to stand in one, this one in particular, where some 75,000 people had died, miserable, naked, terrified, and suffocating, felt like an out of body experience.

The window in the ceiling? That’s the hatch through which the gas canisters were dropped.

In the next room were the reconstructed ovens, made with the original parts.

We would visit Birkenau next, a mile or so down the road.